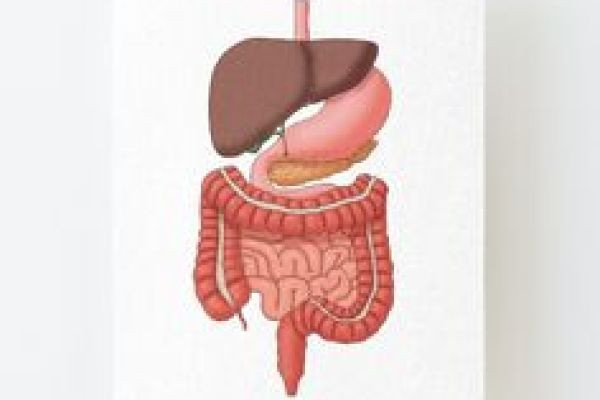

The Digestive System: Structure, Function, and Importance

The digestive system is a complex network of organs and tissues that work together to break down food, absorb nutrients, and eliminate waste. It plays a crucial role in maintaining the body’s overall health and well-being by ensuring that the energy and nutrients needed for cellular function are properly extracted from the food we consume. Understanding the structure and function of the digestive system can provide valuable insights into how the body processes food and how various factors, such as diet and lifestyle, affect digestive health.

Overview of the Digestive System

The digestive system is divided into two main components: the digestive tract (also known as the gastrointestinal tract) and the accessory organs. The digestive tract is a continuous tube that runs from the mouth to the anus, encompassing the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus. The accessory organs, including the salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, produce enzymes and other substances that aid in digestion.

The digestive process is a combination of mechanical and chemical processes. Mechanical digestion refers to the physical breakdown of food, such as chewing in the mouth or churning in the stomach. Chemical digestion, on the other hand, involves the breakdown of food into simpler molecules by enzymes and other chemicals produced by the digestive system.

Stages of Digestion

The digestive process can be divided into several stages: ingestion, propulsion, digestion, absorption, and elimination.

1. Ingestion (Mouth and Salivary Glands)

Digestion begins in the mouth, where food is ingested and broken down through chewing (mechanical digestion) and mixed with saliva (chemical digestion). Saliva contains the enzyme amylase, which starts breaking down carbohydrates into simpler sugars. As food is chewed, it forms a soft mass called a bolus, which is then swallowed and passed down the esophagus through a process known as peristalsis, a series of muscle contractions that move the food toward the stomach.

2. Propulsion (Esophagus and Stomach)

Once the bolus reaches the esophagus, it is propelled toward the stomach. The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the throat (pharynx) to the stomach, and peristalsis ensures the bolus moves smoothly along the digestive tract. At the end of the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter opens to allow food to enter the stomach and then closes to prevent stomach acid from flowing back into the esophagus.

In the stomach, the food undergoes further mechanical and chemical digestion. The stomach's muscular walls churn the food, breaking it into smaller particles, while gastric juices, including hydrochloric acid and the enzyme pepsin, break down proteins. The acidic environment of the stomach helps denature proteins and kill any harmful bacteria that may have been ingested with the food. The resulting semi-liquid mixture, known as chyme, is slowly released into the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter.

3. Digestion (Small Intestine)

The small intestine is the primary site for nutrient digestion and absorption. It is divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine and receives chyme from the stomach, along with bile from the liver and gallbladder and digestive enzymes from the pancreas.

Bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, helps emulsify fats, breaking them into smaller droplets so that the enzyme lipase can further digest them into fatty acids and glycerol. Pancreatic enzymes, such as amylase, lipase, and proteases (trypsin and chymotrypsin), break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins into their simplest forms—glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids.

As the chyme moves through the jejunum and ileum, the nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream through the walls of the small intestine, which are lined with finger-like projections called villi. Each villus contains microvilli, further increasing the surface area for nutrient absorption. The absorbed nutrients are then transported to the liver via the bloodstream for processing, storage, or distribution to the rest of the body.

4. Absorption (Large Intestine)

After most of the nutrients have been absorbed in the small intestine, any remaining indigestible material, water, and waste products move into the large intestine, or colon. The large intestine is responsible for absorbing water and electrolytes (such as sodium and potassium) from the remaining material, forming solid waste (feces) that can be excreted from the body.

The large intestine also plays a role in housing a diverse population of gut bacteria, which help further break down any remaining food particles, produce vitamins (such as vitamin K and B vitamins), and support overall gut health. The waste material is then moved toward the rectum, where it is stored until it is eliminated through defecation.

5. **Elimination (Rectum and Anus)**

The final stage of digestion is the elimination of waste. Once the waste material has been compacted in the large intestine, it is stored in the rectum until the body signals the need to eliminate it. When a person is ready to defecate, the anal sphincters (internal and external) relax, allowing the waste to be expelled from the body through the anus.

The Role of Accessory Organs

The digestive system relies on several accessory organs that aid in the breakdown of food. These include the salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

- Salivary Glands: The salivary glands produce saliva, which contains enzymes (such as amylase) that begin the breakdown of carbohydrates in the mouth. Saliva also moistens food, making it easier to swallow.

- Liver: The liver is responsible for producing bile, a substance that helps digest fats by emulsifying them into smaller droplets. The liver also processes nutrients absorbed from the small intestine and detoxifies harmful substances, such as drugs and alcohol.

- Gallbladder: The gallbladder stores bile produced by the liver and releases it into the small intestine when needed for fat digestion.

- Pancreas: The pancreas produces a variety of digestive enzymes, including amylase, lipase, and proteases, which are released into the small intestine to aid in the digestion of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The pancreas also produces bicarbonate, which helps neutralize the acidic chyme from the stomach, creating a more favorable environment for enzyme activity in the small intestine.

Common Digestive Disorders

The digestive system, while highly efficient, is also susceptible to a range of disorders that can affect its function. Some common digestive disorders include:

1. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): GERD occurs when stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, causing symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain. This condition is often caused by a weakened lower esophageal sphincter, which allows acid to escape from the stomach.

2. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): IBS is a chronic condition that affects the large intestine, causing symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhea, and constipation. The exact cause of IBS is unknown, but it is believed to be related to abnormal muscle contractions in the intestine, heightened sensitivity to certain foods, or stress.

3. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): IBD refers to a group of inflammatory conditions that affect the digestive tract, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These conditions cause chronic inflammation of the digestive tract, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

4. Celiac Disease: Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder in which the ingestion of gluten (a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye) triggers an immune response that damages the lining of the small intestine. This damage impairs the absorption of nutrients and can lead to symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, fatigue, and malnutrition.

5. Gallstones: Gallstones are solid deposits that form in the gallbladder, often as a result of an imbalance in the substances that make up bile. Gallstones can block the flow of bile from the gallbladder to the small intestine, causing pain, nausea, and inflammation (cholecystitis).

6. Diverticulitis: Diverticulitis occurs when small pouches (diverticula) that form in the lining of the large intestine become inflamed or infected. This condition can cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and changes in bowel habits.

Maintaining Digestive Health

Maintaining a healthy digestive system is essential for overall well-being. Several factors can support digestive health:

1. Balanced Diet: A diet rich in fiber, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can promote healthy digestion by supporting regular bowel movements and preventing constipation. Fiber, in particular, helps bulk up stool and facilitates its movement through the digestive tract.

2. Hydration: Drinking plenty of water is important for digestion, as it helps dissolve nutrients, aids in the absorption of food, and softens stool, making it easier to pass.

3. Regular Exercise: Physical activity stimulates the muscles in the digestive tract, helping to move food through the system more efficiently and reducing the risk of constipation.

4. Avoiding Processed Foods: Processed foods, which are often high in unhealthy fats, sugar, and additives, can disrupt digestion and contribute to conditions such as acid reflux and constipation.

5. Managing Stress: Stress can negatively impact digestion by affecting gut motility and increasing the production of stomach acid. Practicing stress-management techniques, such as mindfulness, yoga, or deep breathing exercises, can help support digestive health.